In April 2017, Pepsi released an extended advertisement. The video, which lasted two and a half minutes in its entirety, featured a fictional protest march in the streets of an unspecified city. In the ad’s closing moments, Kendall Jenner emerged from among the protesters to present a Pepsi to a police officer.

The ad succeeded in earning attention: Within 48 hours, it had accumulated 1.6 million views on YouTube. But whereas the brand had hoped to incite a national conversation, it did not foresee the nature of the public’s response.

Activists expressed strong opposition to the ad, claiming it co-opted the spirit of genuine public protests occurring across the country. On social media, viewers voiced similar objections in droves. Even Jenner was devastated by the ad’s reception, saying, “It feels like my life is over.”

Within days, executives pulled the ad from the airwaves. “Pepsi was trying to project a global message of unity, peace and understanding,” the company said in a statement. “Clearly, we missed the mark and apologize.”

The ad was no hasty miscalculation, however. Production on a project of this scale required several months, millions of dollars and the talents of countless professionals. How could a highly choreographed project from one of the world’s largest brands culminate in disaster?

Months after the ad was pulled, Pepsi executives were still asking this very question.

Pressed on the subject in the fall of 2017, longtime Pepsi CEO Indra Nooyi continued to profess her puzzlement.

“I’ve thought about it a lot,” she said. “Because I looked at the ad again and again and again trying to figure out what went wrong.”

Errors in Insight: How Brands Make Strategic Mistakes

Pepsi’s debacle may represent the extreme case of misguided brand activation. But the corporate juggernaut’s error illustrates unsettling risks for businesses of any size.

Indeed, few companies can claim the resources or name recognition Pepsi possesses. While that platform magnified its mistake in this case, the brand has the luxury of meticulously vetting its messaging. If Pepsi’s leadership could be caught off guard by their ad’s reception, no brand should feel entirely insulated from public pushback.

Scarier still, the campaign was likely conceived with sound research in mind – however misguided the resulting video may have been. The ad was probably inspired by a notion that our own work has repeatedly shown: Modern consumers are eager to connect with a brand’s purpose, rather than just its products.

Pepsi’s ad did aim to embrace a higher-order ideal: a sense of unity that Nooyi called “people in happiness coming together.” Few could object to this broad notion and yet the ad was panned universally. The attempt was not entirely lost on viewers, but the ad registered as inauthentic and even exploitative.

Clearly, the devil is in the details where the activation of brand strategy is concerned. Even a vast budget and celebrity endorsements are of no avail if your approach includes fundamental flaws. Moreover, truly exceptional ideas can prove disastrous if enacted poorly.

Even when conceptually sound, brand strategy is often hindered by internal obstacles at the stage of activation. Miscommunication between departments renders a beautiful idea unrecognizable, or team members’ differing expectations are never fully reconciled. These risks are only elevated when a brand attempts something transformative: Breaking with precedent can mean a breakdown in established processes.

In other words, Pepsi is not alone in its struggles: The successful activation of brand strategy is one of the most difficult challenges any company can confront – and far too essential to ignore.

For almost two decades, the Brandtrust team has used social science methods to investigate brand strategy challenges. Our clients have varied significantly in size and confronted a diverse set of difficulties and opportunities. But they’ve all demonstrated a desire to better understand their customers and create strategy accordingly. As Pepsi’s error makes clear, the stakes are too high to do otherwise.

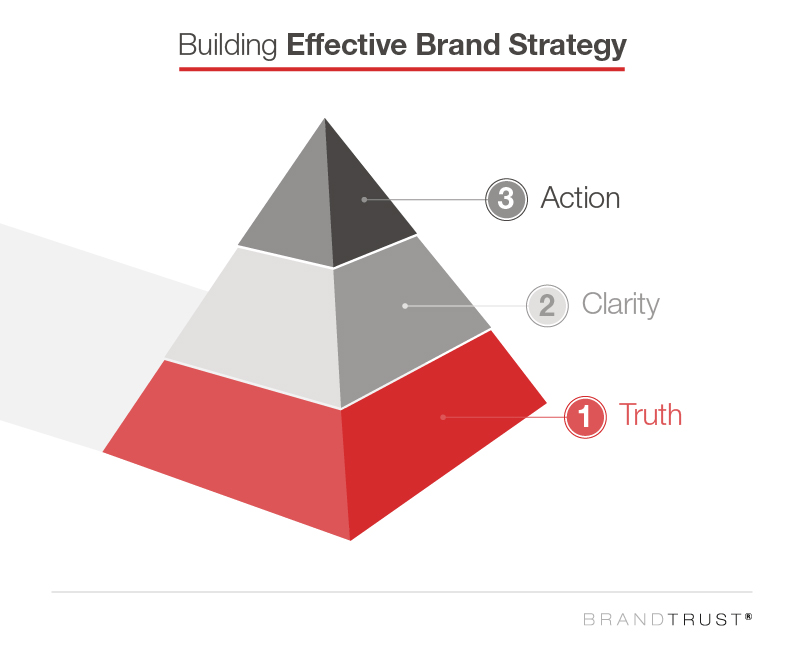

Our experience has given rise to a methodological structure in which to pursue these essential insights: the Truth-Clarity-Action framework. The elements of this approach reveal the emotional and psychological motives of a brand’s target audience and then suggest concrete solutions rooted in those conclusions.

We’ve illustrated the components of this approach elsewhere, but it will be useful to briefly describe the lines of inquiry involved at each stage.

Truth

- What are the true drivers of customer behavior, whether personal or social? In motivating their audiences, brands cannot afford confusion about the causes of desirable (or negative) outcomes.

- Going further, which psychological problems is the brand poised to solve? Think bigger than the practical advantages of a product or service.

- Most importantly, what is the emotional reality underlying the customer experience? Which deep feelings does the brand incite?

Clarity

- Given the conclusions drawn in the truth-seeking stage, where are there possibilities for improvement or innovation? Where could the brand align itself more effectively with its customers’ true needs?

- Additionally, how can the customer’s emotional truth serve as a basis for growing a real relationship? How can the brand create a dynamic of mutual respect, ultimately leading to loyalty?

- Beyond the literal goals customers and brands have in common, what higher order purpose might the business embrace? Is there a basis for lasting trust in shared values?

Action

- Armed with the sense of direction from the first two stages, the brand must engage in the details of activating their strategy. Which tangible changes will make strategy a reality?

- Lofty talk won’t suffice: Telling a brand story is one thing, but living it is another. When your brand’s actions speak for themselves, happy customers will tell your story for you.

- How can we continually improve, test, and refine our conclusions? How do we honor the truth we’ve uncovered already through further discovery?

These questions and concerns are essential but far from simple. How could they be anything other than complicated, given the nuances of the human mind? But when undertaken with expert guidance, the Truth-Clarity-Action approach results in strategic confidence.

Conversely, brands that neglect these considerations are doomed to strategic uncertainty, both in conception and execution. Marketers who refuse to engage in this deeper work are fated to guess if their efforts are making any difference at all – or even if they’re counterproductive.

Unfortunately, even those who seek deeper customer insights encounter obstacles in analysis and interpretation. Understanding the merits of an abstract concept does not guarantee its successful application. Pepsi’s challenges likely reflect this reality: Despite looking in the right places to forge customer connections, the activation of their strategy ultimately distanced them from their audience.

Below, we’ll discuss five common brand strategy activation errors that result from either ignoring customer truths or simply misunderstanding them. Simultaneously, we’ll suggest valuable alternatives that can help brands avert these pitfalls.

Our approach to brand strategy is informed by deep precedent: We’ve seen brands truly succeed in connecting with consumers on human terms. But we’ve also seen tremendous potential derailed by wrong assumptions – a risk no brand need accept.

The Top Five Errors in Activating Brand Strategy

Error No. 1: Getting Lost in Logic

Brand strategy is typically designed with an audience in mind, however broad or targeted that population may be. Accordingly, brands seek to understand the motives of their archetypal customers. What are the mechanics of their decision-making? Which incentive will prompt them to take the desired action?

Marketers are understandably inclined towards logical means of persuasion. When a company publicizes a price drop or a new feature, the underlying assumption is that consumers are rationally considering their purchases. Offer the right deal and customers will respond eventually – right?

But the very necessity of brand strategy implies that consumers are not actually so predictable. In a world in which consumers acted on a rational basis alone, marketing would consist of setting the right price, advertising on as many platforms as possible and waiting for the sales to roll in.

Some companies do take this approach, but it’s rarely sustainable. Eventually, competition cuts margins so thin that profit is painfully limited. Thankfully, there’s a more effective way to reach and retain customers.

In reality, consumers are far from dispassionately rational creatures. In countless ways, instinct and emotion crowd out the calculation in the human mind. As much as 95 percent of brain function is dedicated to nonrational processes, and brands live and die by the associations they forge in this region of cognition.

As a result, a brand strategy must address the consumer’s emotional reality, not just the small slice of their experience that is governed by logic. “We’re the brand with lower prices” won’t suffice. The moment a competitor undercuts you, the entirety of your brand equity will vanish.

Our team’s experience working with Foster Grant reveals the implications of this principle. As the dominant manufacturer of reading glasses in America, the brand might have reduced the needs of its customers to rational terms: Their powers of sight are declining, so they want glasses at a modest price point.

Instead, the brand recognized that emotional barriers prevent customers from making use of reading glasses: Many people who could benefit from reading glasses refuse to wear them. Foster Grant sought our help in analyzing these dynamics, as well as the factors that motivate people who do buy their products.

In in-depth interviews with real customers, our team unearthed the psychological barriers to purchasing readers and the tipping points that help consumers overcome their reservations. In the process, we discovered the resonance of reading glasses as a symbol of aging. Reading glasses are a purchase that requires acceptance, not just an attractive price.

To truly speak to customers, we found that Foster Grant would need to change the association of their product with lost vitality. This conclusion subsequently informed the brand’s long-term strategic outlook and resulted in elevated brand awareness and increased sales.

Had Foster Grant focused on rational appeals exclusively, the brand might have missed the opportunity to better understand and serve its customers.

Error No. 2: Asking the Wrong Questions, Getting the Wrong Answers

If we acknowledge customers often choose and act irrationally, we must grapple with their emotional drivers instead. Perhaps the solution seems simple: Just ask customers how their feelings affect them.

This perspective explains the broad use of traditional research methodologies that focus solely on collecting explicit responses. Unfortunately for the companies who rely on them, these approaches are littered with liabilities.

Business leaders may be blissfully ignorant of well-known issues in polling, such as priming, but academics avoid them like the plague. They can cast a pall of uncertainty over any finding, rendering research suspect.

Moreover, human beings are notoriously incapable of articulating their own true motives. Because so little of our thinking occurs at a conscious level, we supply plausible but inaccurate justifications for our actions. Often, these explanations are entirely rational, whereas the true drivers of our behavior are emotional instead.

As Malcolm Gladwell writes, “While people are very willing and very good at volunteering information explaining their actions, those explanations, particularly when it comes to the kinds of spontaneous opinions and decisions that arise out of the unconscious, aren’t necessarily correct. In fact, it sometimes seems as if they are just plucked out of thin air.”

Accordingly, any brand strategy derived from explicit-feedback methods may not reflect true customer desires. To access the hidden motivations that actually drive consumer behavior, companies will require more nuanced techniques and the patience to pursue real human truth, not counterproductive simplifications.

Error No. 3: Big Talk Above Small Actions

Many companies perceive the need to move beyond transactional appeals in their branding efforts. Countless brands champion their service acumen and deep and personal concern for the satisfaction of their customers. These claims don’t always amount to higher purpose ideals, but they at least suggest attention to universal values, such as respect for those you serve.

As consumers, however, we encounter a chorus of companies making such claims each day. We tire of brands’ lofty promises, in part because they’re so commonplace. Eventually, we grow suspicious – not that businesses will outright deceive us, but that they’ll inevitably disappoint us instead.

In this climate, you can extol customer care all you want, but lasting proof will lie in what you deliver. Brand strategy should guide concrete action, not just communication. And in building real relationships with customers, small actions will matter much more than sweeping statements.

Brands would do well to fixate less on their messaging and focus more on modest opportunities to demonstrate human care for their customers. These small but meaningful alterations in the customer experience can generate significant shifts in sentiment – all at a minimal cost. Conversely, advertising without corresponding action can leave consumers feeling disgusted by the brand’s shortcomings.

How should brands locate meaningful opportunities for improvement within their interactions with customers? Once again, answers reside in the realm of human feeling. The most effective actions will target the most emotionally charged moments of the customer experience. Social scientists have repeatedly found our impressions of experiences are disproportionately influenced by their emotional peaks and valleys.

Will your brand strategy translate to a real application in the customer experience? Are you willing to truly understand what matters to them, and make tangible improvements accordingly? If not, your strategy is just an eloquent abstraction, unlikely to make a difference.

Error No. 4: Spoiling Your Own Story

Whatever the subject at hand, big ideas are much less memorable when we’re forced to focus on their constituent parts. Introduce enough complexity, and even the most beautiful concepts can disappear in a sea of data.

Yet brands frequently forget this basic truth, inundating their audiences with information. When targeted in this manner, customers struggle to recall the details, let alone share them with others.

One powerful example of this principle comes from our work with Intel. Although the company boasted one of the most powerful names in technology, it sought to better understand what performance means to their customers in order to deeply connect their true motivations for purchasing computers.

Through our intensive interviewing process, our team uncovered the emotional aspiration at the core of the customers’ shopping journey. When we shop for new devices, we’re not particularly swayed by specifications. Rather, we hope our new purchase will expand our personal potential, enabling future accomplishments.

As a result of our work, Intel adopted a new storytelling approach rooted in this fuller sense of performance. The company positioned itself not as the hero of its brand story, but as a valued partner instead. The central role went to the customer, who attains purpose and productivity with Intel’s aid.

This brand story is powerful because of its emotional resonance, not its factual inclusions. Intel had a wealth of data at its disposal, from processing power to product dimensions. But to tell its story successfully, the brand needed to put distracting information aside and reveal its true purpose.

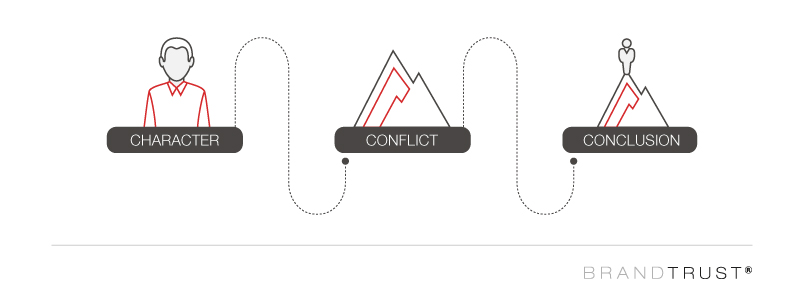

Stories are intrinsic features of human culture: Around the globe, our species relies on them, both for entertainment and existential comfort. There’s a reason for this deep precedent: Neuroscience reveals stories help us process and retain information. Whereas isolated facts require meticulous memorization, a narrative supplies a structure to convey meaning more effectively.

Brands recognize this principle to some extent; many of the world’s most celebrated brands apply it with great success. The basic elements of a great story – compelling characters, essential conflict, and a satisfying resolution – are deeply familiar to us from books and films. Why wouldn’t companies articulate their identities in these terms as well?

In fact, brand strategy need not be retrofitted to reflect these elements: Rather, it can be conceived with these components in mind. If a company’s entire vision is oriented towards storytelling opportunities, the tale it eventually tells is more likely to be both authentic and effective.

Many companies acknowledge the undeniable power of narrative. Yet though they aspire to let their brand stories shine, many brands sabotage themselves unwittingly. They do so by thrusting flattering data points at their target audiences, neglecting key requirements of narrative cohesion.

The quickest way to rob an idea’s power is to isolate or emphasize its constituent parts. Place too much focus on the particularities, and the holistic concept will be rendered incomprehensible.

Error No. 5: Inauthentic Ethics

Much like brand storytelling, brand purpose has recently been the subject of increased emphasis among marketers. This trend likely stems from the success of companies infused with social purpose, from TOMs Shoes to Warby Parker.

As we noted in connection with the Pepsi debacle, consumers are attracted to shared values. When a brand’s principles resonate as much as its products, customers have a basis for lasting loyalty. If a brand stands for more than profit, it can insulate itself from competition and shrinking margins.

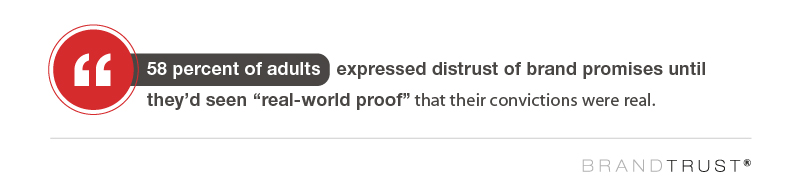

But higher-order purpose must stem from authentic conviction, not a desire to mask profit motive in more palatable terms. And as more brands adopt purpose-oriented messaging, consumers are growing more skeptical accordingly.

One recent study, distinguished by its use of in-depth personal interviewing and methodological rigor, found significant evidence of this growing cynicism. According to their findings, a central issue is the “arrogance” of brands that claim a lofty purpose without being worthy of it. As a result, 58 percent of adults expressed distrust of brand promises until they’d seen “real-world proof” that their convictions were real.

Additionally, brands must remain true to their stated values as they grow. Facebook, which has historically espoused the value of interpersonal connections, recently reckoned with this challenge. As advertising and sponsored posts displaced content from real friends, the company’s core purpose receded from view. Later, concerns about fake news and data misuse caused the brand to publicly recommit to its mission.

True brand purpose flows from a unique intersection of consumers’ psychological needs and a company’s character. A brand cannot attach itself to an arbitrary cause to bolster its public perception. Rather, it must seek to understand areas of common ground with its audience and take genuine action accordingly.

Confidence in Your Conclusions: Steering Clear of Strategic Risks

These errors in conception and activation may frequently produce strategic misfires, but their destructive effects can be difficult to observe. Indeed, organizations often struggle to perceive real troubles in their midst, because leadership is so steeped in the assumptions underlying current strategy.

To truly recognize shortcomings in brand strategy, a business must adopt a beginner’s mind framework for investigating challenges. This perspective can be humbling and even disorienting, with presumed realities revealed as assumptions instead. But it’s the only proper beginning for a process that will replace misconceptions with meaningful insight.

Brands need not – and should not – undertake this difficult investigation alone. If your company is willing to demonstrate the humility needed to scrutinize its core assumptions, you deserve a more experienced partner in that process.

The Brandtrust team can introduce new research rigor and strategic guidance to your journey of brand discovery. Along the way, we’ll do more than simply avert potential pitfalls.

Our approach will proactively identify opportunities for meaningful change that emerge in our research. We’ll then help develop and assess tactics designed to achieve your stated goals. In this manner, areas of improvement become clear opportunities, rather than undiagnosed liabilities.

To discover how we’ve employed this approach in partnership with many of the world’s most respected brands, explore our past work in more detail.