Green Mountain Coffee Roasters enjoyed tremendous growth. From its humble beginnings as a coffee shop in 1981, the business bloomed into an enterprise worth more than $100 million. But, by 2000, serious challenges began to emerge. The business’ very success could have been its undoing: If Green Mountain failed to increase efficiency as it scaled, its newfound size might suffocate growth.

Founder and CEO Bob Stiller had definite goals for improved performance. Chief among them was his “25 Cent Challenge,” a quest to reduce operating costs by about a quarter per pound of coffee sold. Stiller might have targeted problem areas in his company, focusing on existing barriers to his vision. Instead, he took precisely the opposite tack.

Stiller and the company leadership employed a method called Appreciative Inquiry. At its core, Appreciative Inquiry seeks to identify the best in individuals and organizations, uncovering new possibilities by embracing existing strengths. Accordingly, appreciative approaches emphasize hope and open discovery, rather than fixating on thorny issues to be addressed. Instead of harping on existing inefficiencies, Stiller called on executives to acknowledge what Green Mountain was doing well – and urged them to apply those strengths more broadly.

The results of this undertaking surprised even Stiller. Following this appreciative process, the business streamlined purchase orders for all buying activities, allowing the company to obtain better prices and optimize payables processing. The team also envisioned updates to order tracking and delivery logistics, ultimately enhancing cash flow. The “25 Cent Challenge” was successfully met.

These solutions did not emerge immediately, but the team’s engagement with the appreciative philosophy eventually revealed the best way forward. While the journey required some patience at first, Green Mountain executives were soon eager for more.

“We identified the one best path in each process,” said former CFO Bob Britt, “and asked, ‘Why don’t we do this with everything?’”

Appreciative Inquiry: Seeing Strengths

With over 20 years in research and brand strategy consulting, our Brandtrust team has seen Appreciative Inquiry produce similar outcomes – and enthusiasm – for many kinds of organizations. At a fundamental level, Appreciative Inquiry demands a willingness to shift perspective, moving from an emphasis on problems to a focus on potential.

This conceptual realignment can sometimes be challenging: Modern business culture tends to promote frenzied problem-solving, often at the expense of celebrating success. But once a team embarks on an appreciative journey together, the resulting creativity resolves any lingering skepticism.

Moreover, a single application of the appreciative perspective can pave the way for many more. As Mr. Britt of Green Mountain suggested, this approach can shed light on a wide variety of organizational concerns. From massive corporations to growing nonprofits, we’ve seen appreciative methodologies produce groundbreaking change for a diverse array of teams.

Research evidence confirms our experience: One meta-case analysis of 20 Appreciative Inquiry case studies observed powerful changes in many kinds of organizations, from Fortune 500 companies to Catholic schools. Most striking of all, 35 percent of cases yielded “transformative change,” or a paradigm shift in the organization’s attitudes and operations.

Some such case studies present particularly compelling support for appreciative approaches. In 1996, financial services giant GTE trained thousands of its employees in the art of Appreciative Inquiry. Over the next year, the company was stunned by the outcomes it enjoyed, attributing the following changes directly to its adoption of appreciative methods:

- Employees’ support for GTE’s business direction jumped 50 percent.

- Employees’ perception that information was shared openly increased by almost 140 percent.

- GTE improved its credit verification process, resulting in $3 million collected in 1996. The team also improved its payment process, saving $7 million to $8 million annually.

- The company also developed a new way to automate the insufficient funds process, saving $4 million in 1996.

As a result of these changes, GTE earned the award for best organization change program from the American Society for Training and Development.

But just a few years before massive corporations began using Appreciative Inquiry to transform their businesses, appreciative methods were little more than an intriguing hypothesis. Appreciative Inquiry first emerged from the efforts of a doctoral student, David Cooperrider, and his adviser, Suresh Srivastva, in the 1980s.

Drawing from a number of social science disciplines, Cooperrider devised an innovative approach to assessing the Cleveland Clinic, a hospital renowned for its quality of care. In a research paper that would eventually become his thesis, Cooperrider accentuated the organization’s strengths, illuminating corresponding areas of potential. The phrase “Appreciative Inquiry” first appeared in a footnote of that report.

Since that time, appreciative techniques have been adapted and refined for use in a range of settings. Organizations from the United Nations to NASA and Avon have employed Appreciative Inquiry successfully, defining new areas in which the appreciative perspective applies. Their successes reflect goals that many businesses share, from optimizing collaboration between departments to revitalizing company culture.

Since its modest beginnings, however, the heart of the theory has remained steady: When you look for the best in people and organizations, new ways of thinking and being become possible. By practicing true openness and optimism, organizations uncover new aspirations – and potential they never dreamed they possessed.

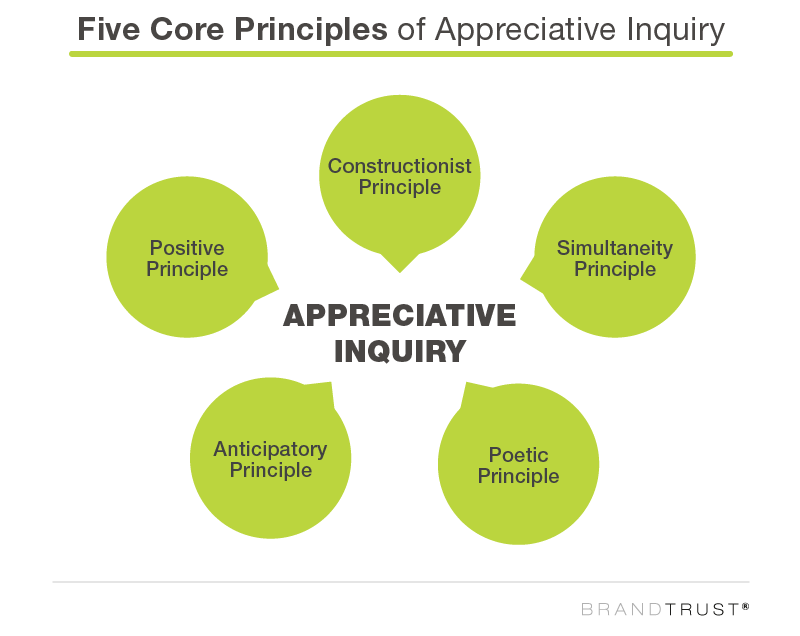

Indeed, Cooperrider and Srivastva explicitly identified five key principles of AI, concepts that would inform every aspect of their work. At Brandtrust, we find these principles deeply familiar, because they resonate so much with our own social science expertise.

The Constructionist Principle: Reality as we know it is a subjective state, rather than an objective one.

In approaching any challenge or opportunity, fact-gathering may seem like the obvious first step. After all, any eventual conclusion must be rooted in reality, so accurate data is an essential prerequisite for sound decision-making.

Yet, in our thirst for information, we stumble into a rigid, positivist view: that there is one objective reality, ready to be revealed. However, human experience continually proves that our perceptions are colored by emotion, biases, and situational contexts. It may be comforting to regard ourselves as rational creatures, but our sense of the world is continually shaped by nonconscious influences.

The constructionist principle of Appreciative Inquiry embraces this complexity, acknowledging that the world we see is filtered through our personal and organizational preconceptions. Individually and as a part of larger communities, we construct the reality we inhabit through our subjective perspectives.

For organizations, the implications of this concept are twofold. First, Appreciative Inquiry provides a singular venue in which to challenge one’s personal biases, inviting differing truths to commingle in a collaborative process. When others share understandings we did not possess ourselves, we recognize the limits of our own subjectivities.

Second, we find that reality is collectively constructed – and, therefore, constrained – by the organization. If the group considers a problem intractable, it will be. But if the group can broaden its horizons with an entirely new approach, unseen solutions become visible. A new, more hopeful reality can begin to take root.

The Simultaneity Principle: Inquiry is intervention and creates change. The moment we begin to ask a question, we begin to create change.

In the traditional view of organizational change, inquiry and action represent separate phases. First, a team poses questions, gathers answers, and draws conclusions. Subsequently, the organization enacts whatever concrete changes seem necessary.

The simultaneity principle refutes this dichotomy. In AI, questions are interventions in their own right because they determine the trajectory of change to come. After all, if a team’s questions revolve around a single topic, they foreclose meaningful discussion of anything else. Therefore, inquiry and change occur simultaneously: The right question can constitute a paradigm shift.

For this reason, some scholars discuss Appreciative Inquiry as a form of “Action Research,” emphasizing that investigation and implementation occur simultaneously. Given the principles and processes that the appreciative approach demands, true participation inherently entails growth and change.

That change is generative in nature: For organizations, new understandings and attitudes are profound assets in their own right. In this sense, Appreciative Inquiry narrows the gap between insights and impacts; they are simultaneous, rather than sequential.

At Brandtrust, we frequently work with clients to arrive at more beautiful questions about their own businesses. Indeed, when organizations question their most basic assumptions, adopting a “beginner’s mind,” radical improvement begins.

In the context of AI, the questions we pose most often pertain to unrecognized strengths. Simply asking what your organization does best could propel it to new heights.

The Poetic Principle: Human organizations are an open book, and their stories are constantly being co-authored. Pasts, presents, and futures are endless sources of learning, inspiration, and interpretation. We have a choice about what we study, and what we study changes organizations.

Businesses, Appreciative Inquiry posits, are like great books: They are rich enough to be revisited. Each time we take another look, a different interpretation emerges. Moreover, the narrative speaks to enduring dimensions of the human condition. The story describes not just one situation, but what it means to be alive more generally.

These notions, collectively called the poetic principle, suggest that we have good reason to explore an organization’s patterns, even if they’ve been scrutinized before. Perhaps a new discussion (this one framed in terms of strengths) will shed new light on past events and current initiatives.

Your organization is composed of human beings, each of who possesses great depth. Don’t assume any topic has been exhaustively covered because there’s always another layer of perspective to reveal.

Additionally, a single incident or experience could reveal a larger truth about your organization, just as a concise poem can speak volumes about the human condition. In our own work with organizations, we emphasize deep interviewing techniques, accessing the emotional realities that define the experiences of team members and customers. In our 20-plus years of experience, we’ve found that using immersive strategies and gathering penetrating insights from a few individuals is often more helpful than getting surface-level responses from hundreds.

The Anticipatory Principle: Human systems move in the direction of their images of the future. The more positive and hopeful the image of the future, the more positive the present-day action.

It’s often said that our past actions suggest future behaviors. Yet, Appreciative Inquiry proposes a very different perspective: Our view of the future dictates our present choices.

The anticipatory principle recalls Henry Ford’s famous axiom, “Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t – you’re right.” If members of your team anticipate a brighter future predicated on your collective strengths, their behaviors will support that success. By contrast, team members who question an organization’s potential are less likely to supply their best efforts, consciously or otherwise.

As the appreciative process invites team members to explore organization strengths together, participants collaboratively create a vision of shared potential. Because this vision emerges from open dialogue and depends on consensus, it will be far more powerful than a corporate strategy handed down from the higher-ups.

In our work with clients, we frequently explore the concept of “brand purpose,” which captures a company’s reason for existing in the lives of employees and customers. This purpose encompasses a brand’s higher-order mission, cementing bonds of loyalty and trust with its customers.

Our work also engages a related notion: “brand promise.” We use this term to describe a brand’s most fundamental value proposition: What better future does the brand make possible, and why do customers care?

The anticipatory principle clearly concerns both these concepts. If your organization is oriented toward a shared mission – and truly believes it can be accomplished – your aspirations will fuel your achievements. If your business believes it can impact customers positively, it will manifest that conviction in myriad ways.

But the anticipatory principle also highlights a crucial recognition: Your organization’s future lies in the feelings, ideas, and attitudes of its people. Brand purpose and promise must be more than mere talking points. Rather, they must characterize your culture, allowing every employee to feel ownership of your organization’s vision.

The Positive Principle: Momentum for large-scale change requires large amounts of positive affect and social bonding. This momentum is best generated through positive questions that amplify the positive core.

In some ways, the positive principle may be the most basic – and integral – concept involved in AI. It suggests that sustained organizational change depends on positive effect and social bonds between individuals. Without warmth, camaraderie, and a sense of shared trust, attempts at transformative change will face skepticism and resistance.

So how can organizations increase mutual respect among team members? And once individual strengths are acknowledged, how can they be effectively combined in a collective process of improvement?

Once again, the answer lies in asking the right questions, this time about what members of your organization do well. The more positive the framing of the inquiry, the better. What makes your colleagues great at what they do? How are they invaluable to the organization at large?

Too often, corporate culture emphasizes criticism when assessing performance: Managers emphasize setbacks and failures more often than they commend success. The positive principle is the appropriate antidote, reminding everyone that solutions will stem from our strengths, not our weaknesses.

From Principles to Practice: Our Expertise

As we close our discussion of Appreciative Inquiry, we hope the flexibility of the appreciative perspective is clear. Beyond any single application, the appreciative approach provides a means to reimagine your organization’s path forward, illuminating potential at every turn.

Furthermore, an appreciative approach can transform the way in which you assess your organization’s efforts. As your team goes about its daily work, are they committed to a bold vision for the future, as the anticipatory principle suggests they could be? Bearing in mind the positive principle, is your business actively fostering mutual respect and appreciation among employees?

More generally, the principles of Appreciative Inquiry help us put higher aspirations at the heart of our organizations. When we discover the positive potential embedded in our brand DNA, we have a new standard to aim for each day. When teams strive together toward a better future, their work is infused with powerful purpose.

What is the better future that your brand can bring about? No question is more essential to your organization’s identity – or its destiny.

To explore the transformative potential of the appreciative perspective, consider reviewing our case studies or get in touch.