In 2010, psychologists T. Bettina Cornwall and Anna McAlister published research entitled “Children’s Brand Symbolism Understanding” in the journal Psychology and Marketing. In the months that followed, public outcry would obscure many of their study’s most interesting outcomes.

The experiment assessed 38 Australian children between the ages of 3 and 5, asking them if they could identify a number of corporate logos. Previously, researchers had assumed symbolic recognition would be impossible at this age. Cornwall and McAlister proved otherwise. The kids were shockingly adept at identifying logos, particularly for brands such as McDonald’s and Disney.

In response to these results and similar studies, horrified parents mobilized to protect their children’s minds from corporate influence. A campaign to retire Ronald McDonald gained momentum, suggesting the kid-friendly mascot was contributing to childhood obesity.

Although impassioned, this debate about corporate symbols largely ignored the more nuanced – and compelling – conclusions drawn by its authors. According to Cornwall and McAlister’s conclusions, the children’s capacity for logo recognition was dependent upon their emotional connections to certain brands.

“My feeling is that a lot of this has to do with positive emotions,” McAlister noted. “Children recognize things that are self-serving and enjoyable.”

The study did not suggest that children recognize logos and mascots and come to love brands subsequently. Rather, it suggested precisely the opposite phenomenon: Logo recognition was only the function of pre-existing emotional associations.

Indeed, the children who took part in the study expressed the emotional significance of the brands they could recognize. When asked what they thought of McDonald’s, children provided responses such as, “McDonald’s has a playground so you can play there and everyone likes you.”

A Symbol Must Stand for Something

It’s understandable that the real importance of this much-discussed study has been overlooked. Parents are predictably concerned about corporate influence: It’s unsettling to see kids recognized logos before the letters of the alphabet.

Moreover, this perspective resonates with a familiar narrative of advertising’s evils: Companies flood the human brain until it craves the product in question.

Much can and should be said about ethical advertising practices. But this focus on the visibility of brand symbols ignores the deeper connection the children actually described. Brands can derive great value from their logos, but only when they stand for something.

The dominance of the McDonald’s brand lies not in customer’s ability to recognize Ronald. Whether consumers are 5, 15, or 50, the company’s power consists of the psychological associations that the Golden Arches incite.

Earlier this year, our team of researchers employed an interviewing technique we’ve termed as “Narrative Inquiry” to explore consumers’ emotional associations with some of the world’s most prominent brands.

When we studied McDonald’s specifically, our results suggested an interesting link to McAlister’s study. When we uncovered an emotional basis of consumers’ connections to McDonald’s, happy childhood memories were a common cause of continued brand loyalty.

Another common association was a sense of kindness. In the minds of customers, the McDonald’s brand comes to stand for small moments of interpersonal warmth, from sharing fries to romping through the play area together.

These associations are powerful drivers of behavior, the true advantage inherent in the McDonald’s brand. No single advertising appeal can instill emotional attachments of this kind.

Some marketers, however, are content to see brands in more shallow terms. Asked to describe a brand’s basic properties, they’ll offer a literal definition such as, “A name, term, sign, symbol, or design, or a combination of them, intended to identify the goods or services of one seller or group of sellers and to differentiate them from those of competitors.”

This conception has the virtue of simplicity but offers few productive insights. Aesthetic differences may permit customers to identify alternatives, but they won’t be the basis of any true connection. Indeed, the value of a sign is what it signifies.

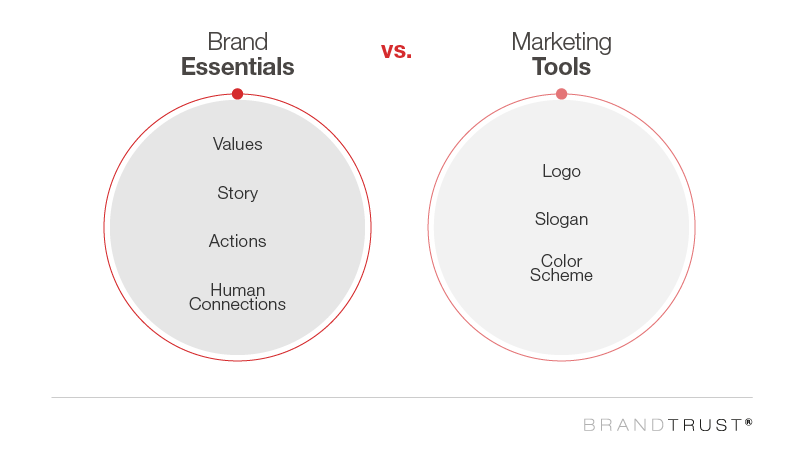

Clearly, any productive discussion will require a broader notion of what a brand entails. If we are to learn how and why some brands succeed, we must move past the superficial elements of branding (logo, color schemes, taglines) and toward factors that actually influence consumer behavior.

Children are not the only ones who form complex associative webs around various brands. Although adults may claim to act on a rational basis, we are also moved by deep emotional and psychological attachments to the brands we trust.

In connecting with consumers on this powerful basis, strong brands transcend visual or auditory signifiers. To speak to the deep needs of customers, a brand must embody a company’s essence – and more importantly, its purpose.

Through nearly two decades of work with many of the world’s most distinguished companies, our team of researchers and social scientists has explored how brands function in the minds of consumers. Our experience has revealed not only how brands shape consumer feeling and behavior but also how brands can activate these insights.

But to enjoy the clarity and opportunity afforded by this approach, marketers must be willing to explore how strong brands are actually grown. That means wading into unfamiliar territory and grappling with notions more complex than a simple logo.

When a company engages the factors that actually shape its brand, real change is possible. Here are some factors that define the nature of your brand far more than your logo.

Your Brand Is Your Business

To establish the emphasis that your brand deserves, it’s helpful to assess the defining elements of any company. What are a business’ defining characteristics, both internally and in its representation to the broader public?

We may be inclined to enumerate concrete assets: Resources, products, and personnel likely come to mind. But to what extent are any of those components distinctive or immune to replication?

If a competitor emerged tomorrow utilizing similar assets and tactics, what would meaningfully distinguish your business from theirs in the minds of customers? Perhaps, in this scenario, you’d offer lower prices to keep customers. But competing in a price war would only reveal that your products are not actually superior – and painfully reduce your margins.

If your company has existed for some time, you might be inclined to protest on the basis of your track record. Surely your business would survive the upstart’s challenge: You’ve established credibility with customers and built a reputation. How could a new company compete with that?

Notice a key change transpiring in the course of this discussion: As soon as real challenges emerge, we look to a company’s brand as a source of resilience. The hard assets of a business can be replicated or replaced, but that’s not true of the emotional and psychological associations that build in customers’ minds over time.

Therefore, your brand is the very essence of your business, not a secondary concern. If you hope to navigate competition and other obstacles that inevitably arise, your brand will be key to sustainability. Your future lies in the feelings of your customers.

Your Brand Is Your Story

If a business is inseparable from its brand, it’s important to understand how customers form emotional impressions of the companies they encounter. Our work consistently reveals that one form of communication triumphs above all others in the human mind: storytelling.

The power of narrative is well-established: We’re drawn to stories compulsively and recall them with more accuracy than isolated bits of data. To distinguish themselves in customers’ minds, brands must harness the potential of their own stories.

Unfortunately, many companies neglect this approach altogether, assuming the simpler path is to assert single facts. “Lasts twice as long!” or “25% more free” may catch the eye momentarily. But these statements reveal nothing about a company’s character, aside from its eagerness to sell.

But when a customer and company are joined as characters in a single story, a brand connection can form. In these cases, the customer surmounts some challenge with the brand’s assistance, achieving a desirable outcome.

Consider the child’s comment about McDonald’s: In explaining why she felt warm about the brand, she automatically adopted the mode of storytelling. The customer is the protagonist of the narrative (“Everybody likes you”), but her experience reveals the power of story to cement positive brand associations.

What conflict can you help your customer overcome? Which psychological need would your story serve? These questions are integral to how your brand will be perceived.

Your Brand Is Your Values

Your brand elevates your product beyond the realm of indistinct commodities, providing a basis for customer identification. But that connection must consist in shared ideas rather than transactional benefits.

The modern consumer has a vast array of options at his or her disposal – and more tools than ever to evaluate choices critically. The internet enables us all to investigate the companies with whom we do business and choose differently if we don’t like what we find.

In this climate, a brand’s principles are paramount. We care less about the particular product being foisted upon us and more about the values espoused by the company in question. After all, given the vast availability of alternatives, the brands we choose reflect something about who we are as well.

Notably, brands don’t demonstrate their values by practicing arbitrary acts of charity. If an altruistic endeavor seems inauthentic or exploitative, “cause marketing” can backfire publicly. Additionally, some studies suggest charitable missions can be counterproductive to internal employee morale if they feel it’s merely symbolic.

Authentic values emerge from the intersection of a brand’s identity and the convictions of customers. But when this alignment is achieved, the expression of these values becomes more intuitive across new channels and other opportunities.

Consider the example provided by Zappos, a brand beloved by customers for its commitment to care for customers – an ethical devotion in its own right. To achieve this distinctive reputation, the company employs a set of “omni-values,” core principles that permeate every element of the business’ operations.

These principles ultimately improve the experience of customers, but they’re really encouragements to do meaningful work. Employees are urged to “pursue growth and learning” and “build open and honest relationships with communication.” When earnestly followed, these values are a path to purpose.

To achieve the results that Zappos has enjoyed, however, values must be practiced rather than merely preached.

Your Brand Is the Little Things You Do

Few brands make patently false statements about the tangible aspects of their businesses. But when it comes to more subjective elements of the customer experience, hyperbole is unfortunately common. When the vast majority of brands tout their exceptional service acumens, such claims prompt skepticism.

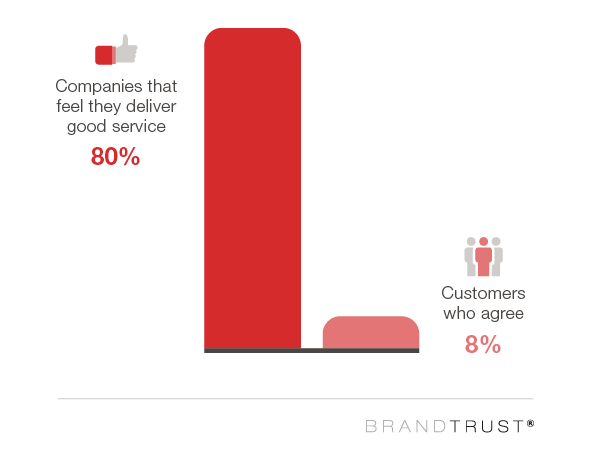

Some brands are simply mistaken about the quality of their service, as opposed to intentionally deceptive. When 80 percent of companies feel their customer experience is good but merely 8 percent of customers agree, a deep disconnect is obvious.

The combination of these dynamics represents a grim brand challenge. Most customers are understandably cynical about language and finding their fears substantiated by subpar service. Where might feasible solutions lie?

Clearly, great brands have always been built on more than rhetoric – now more than ever in our “attention economy.” Conversely, they succeed through modest but meaningful actions that serve the emotional needs of customers rather than sweeping statements.

Where might such relevant moments be located for your customers? Simply put, the most influential interventions will target aspects of the customer experience in which emotions run high. Which small changes could meet a psychological need for your audience, either by easing anxiety or communicating real care?

This kind of inquiry may reveal key areas of potential improvement, but those insights will hinge entirely on the buy-in of employees. If your team doesn’t embrace the power of the small changes prescribed, you’ll be another brand making claims you can’t back up.

Your Brand Is a Human Connection With Customers

Consider the brands you love best and how you’d describe them to an acquaintance. At first, you might explain the literal components of the products or services they provide. But as you continued to explain your loyalty, you’d likely gravitate toward more emotive terms: dependable, truthful, and honorable.

These descriptors are plainly positive, but they also have something else in common: We typically use them to describe human beings. The most powerful brands achieve a kind of anthropomorphism – we relate to them as we would a friend.

How are these connections actually constructed? Because they are deeply personal, the details of brand relationships differ in each case. In every valuable brand connection with customers, one of the essential ingredients is trust.

In fact, trust is an essential element of each of the brand factors we’ve described above. Your brand is built on storytelling, shared values, and meaningful actions, but none of these elements matter if your brand can’t be trusted.

In the absence of trust, your brand’s human character can never emerge or be truly appreciated. To your audience, your triumphs will be short-lived, and your errors will be crippling. So how can this prerequisite to success be attained?

Over decades of experience, our team has developed a framework to engage and encourage customer trust and grow related elements of your brand simultaneously. We call it the Integrity-Competence-Vulnerability structure, and it holds the keys to building a brand with which customers can truly bond.

We’ve explored these notions at great length elsewhere, unpacking the ideas behind each adjective. If you’re interested in ensuring your brand can be trusted, we invite you to explore our work on the subject.

Your Brand Is Worth Building

For the marketer willing to engage them, these concepts reveal real opportunities. But every possibility comes with its attendant challenges, and the nuances of the human mind should not be underestimated.

With a new understanding of your brand’s constituent elements, you’re likely eager to move toward strategy. But more rigorous exploration must come first. Any plan worth executing will be rooted in real truth, not the shaky ground of assumption.

Our team brings extensive research experience to the table, permitting deep exploration of your most vexing business challenges. Our methodologies avoid the frequent pitfalls of other market research methods, so you’ll enjoy a level of insight your competitors lack.

Once we define the human truth at the heart of your brand’s potential, we’ll move to provide strategic recommendations as well. Insight is only as valuable as its eventual application, and our experts can aid your brand with both.

Once you acknowledge the complexity and opportunity inherent in your brand, you can’t simply resume a superficial approach. We’ll help you grow a brand with purpose and potential that goes deeper than mere symbols.