When asked to describe the “jobs-to-be-done” approach to understanding customers, Clayton Christensen remembers the milkshake.

A major fast food chain had turned to Christensen and his Harvard Business School colleagues for help. Despite much market research and meticulous product testing, milkshake sales simply wouldn’t budge. This stagnation was inexplicable: According to the chain’s survey data, their current milkshake formulation perfectly matched the preferences of their target audience.

Intrigued by this dilemma, a colleague of Christensen’s camped out in local franchise, observing who purchased milkshakes over the course of a full day. He recognized an interesting pattern: Roughly 40 percent of milkshake purchases occurred before working hours. Professionals would order them to go, intending to consume them during their morning commutes.

This phenomenon made sense on a functional level. Milkshakes were a light morning treat that could fuel folks through lunch and be easily consumed with one hand on the wheel. But the product also served a different – and deeper – purpose: Distraction from the monotony of the daily drive.

In other words, Christensen concluded, the milkshake had a job to do. The chain could reformulate its milkshake to better serve this purpose, arriving at a thicker and more interesting formula packed with fruit, built to last the full morning commute. Previous attempts to alter the milkshakes had focused on reported customer preferences, rather than the underlying needs the product could meet.

“The jobs-to-be-done point of view causes you to crawl into the skin of your customer and go with her as she goes about her day,” Christensen later explained, “always asking the question as she does something: Why did she do it that way?”

Jobs-to-be-Done: Purpose In Products and Services

As the milkshake anecdote suggests, Christensen’s jobs-to-be-done framework represents a fundamental shift in the way businesses conceive of their customers’ motives. A celebrated academic, he found himself baffled by the sheer quantity of products and services that never found a consistent consumer base.

Indeed, Christensen’s research indicated that as many as 95 percent of new products fail in a given year. Clearly, existing market research techniques left much to be desired in terms of anticipating real behavior. For all their nuanced audience segmentation and demographic analyses, the world’s biggest brands struggled to predict what consumers would actually buy.

In Christensen’s view, companies relied too heavily upon consumer categories as a basis for understanding individual choice. “The fact that you’re 18 to 35 years old with a college degree does not cause you to buy a product,” Christensen noted. “It may be correlated with the decision, but it doesn’t cause it. We developed this idea because we wanted to understand what causes us to buy a product, not what’s correlated with it.”

What causes us to buy a product, Christensen posited, is a need we need to meet or a problem we need to solve. We choose products or services because they can perform jobs that need doing in our lives, whether those functions are tangible or highly complex.

No demographic characteristic compels you to consume a milkshake. Neither does some intrinsic feature of the milkshake drive your behavior. You buy it because it can perform a specific duty, such as injecting some small measure of pleasure into the monotonous drive ahead. Accordingly, Christensen described consumers as “hiring” a product or service: Everything we purchase performs for us in some manner.

Naturally, Christensen’s work resonates deeply with our own approach to understanding customer behavior. When our team first discovered Christensen’s scholarship, the correspondence between our interests seemed uncanny, like meeting the twin we never knew we had. After nearly 20 years of deep inquiry into the factors that shape human choice, we too believe that brands thrive by meeting their customers’ implicit needs – and often their nonconscious ones.

Indeed, our team has repeatedly observed how customers regularly respond to instincts that never rise to the level of conscious contemplation. Many of our methodological approaches are designed precisely to access these implicit insights, so that brands may better connect with and serve their customers. The jobs-to-be-done model of consumer behavior aligns beautifully with our processes: We strive to identify customer’s deep desires so that brands can deliver as never before.

Moreover, the jobs-to-be-done framework reinforces our conclusions about the value of purpose-driven companies. In fact, Christensen has written frequently about “purpose brands,” businesses constructed entirely around a single – if abstract – job to be done.

When a family needs a warm and wonderful vacation together, no one does the job like Disney. Making a new home of your own? No company springs to mind like IKEA. When your brand is synonymous with an aspiration that customers hold dear, they’ll “hire” you every time.

Accordingly, modern brands must identify the material or psychological jobs they perform on behalf of their customers. Our team engages in this work every day, collaborating with many of the world’s most illustrious companies to perceive and meet consumers’ needs.

Before we leap to conclusions about a product’s true utility, however, we must first embrace a greater degree of nuance. Inevitably, products must meet several needs concurrently, serving customer desires on many levels. Thankfully, the jobs-to-be-done framework engages this multiplicity as well.

Great products possess thematic coherence: Their various features and functions are ultimately anchored in guiding human truths. But even if we identify the overarching job a particular product must do, it’s impossible to translate that vision directly to design. Questions arise immediately: Which tangible characteristics will be conducive to this broader goal?

In other words, it’s helpful to understand that milkshakes must alleviate boredom, converting the empty dread of a commute to a small moment of enjoyment. But Christensen’s real genius consists in observing the emotional and practical implications of that conclusion – the other kinds of needs that stem from the milkshake’s central purpose.

No product has a single job to do, therefore, but many. To attain true jobs-to-be-done success, a product must meets its customers’ functional, emotional and social needs simultaneously.

The Customer Needs Network: Delivering on Multiple Levels

By synthesizing Christensen’s work along with our own team’s expertise, we’ve defined major job categories that products must perform in order to satisfy customers. This typology should not suggest fragmented product requirements, but rather a roadmap for coherent product development and marketing strategy. Indeed, when executed correctly, these various jobs serve to reinforce each other, creating holistic harmony.

Emotional Jobs: How Does the Product or Service Make the Consumer Feel?

Our fascination with emotional impacts is no secret: We’ve devoted a large body of research to how consumers’ feelings – conscious or otherwise – inform their behaviors. Accordingly, products and services must meet specific emotional needs for the people who purchase them. In many ways, customer trust and loyalty depend on the execution of these emotional jobs above any other criteria.

Consider granola bars, which 70 percent of Americans regard as healthy. Unfortunately, less than a third of nutritionists agree; these bars are frequently made with sugar and lacking in genuinely nutritious content. And yet these bars perform their emotional jobs extremely well: Guilt-free craving elimination, plus the self-congratulation of making a healthy choice. These feelings drive sales, not what’s listed on the label.

Social Jobs: How will the Consumer be Perceived by Others?

Few purchases occur in a vacuum: When we invest in a product or service, we do so as consumers in a social context. Accordingly, the things we buy communicate our values to those around us. Consider the social jobs performed by our clothing: If a particular logo is emblazoned upon a nondescript t-shirt, it suddenly projects sophistication and style. When we check our outfits in the mirror, we do so to simulate the perspectives of others.

Of course, a product’s social job may be noble as well. When we support a brand’s social purpose, our purchases signal our commitment to their cause (such as the altruism of Tom’s Shoes). When a product helps us express the best parts of ourselves to the wider world, it’s performing its social job perfectly.

Functional Jobs: What Does the Consumer Need the Product or Service to Do?

Functional jobs refer to specific outcomes or changes a product makes possible, the tangible tasks an item is designed to perform. These jobs represent the minimum litmus test for whether something “works” – or whether the customer wants his money back.

Functional jobs may be best described by a famous aphorism from Harvard Business School professor Theodore Levitt. “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill,” Levitt declared. “They want a quarter-inch hole!” The quarter-inch hole is the functional job the drill must do.

Overall Jobs: What is the Actual Progress the Consumer is Trying to Make?

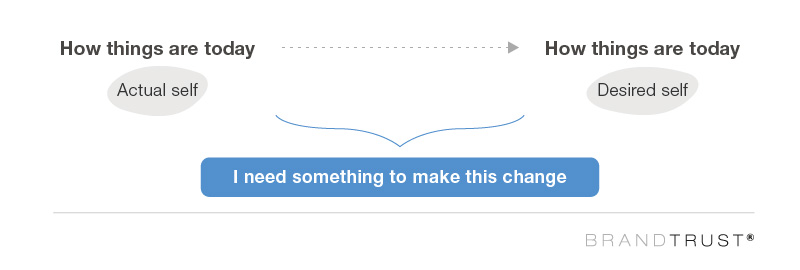

Overall jobs address human beings’ existential desires – in the present and for the future. As we navigate the world, we find cause for dissatisfaction or identify room for improvement. Consumers “hire” the item that will help them shrink the gap between their current experiences and their ultimate aspirations. We hire the items that help us progress towards the version of ourselves we most desire.

As their title suggests, overall jobs represent the synthesis and expression of a product’s emotional, social and functional purposes. To effectively perform its overall job, a product’s other roles must exist in alignment.

Given these jobs-to-be-done on various levels, product attributes must correspond to a nuanced array of customer needs. But one essential advantage of the jobs-to-be-done framework is that it facilitates collaboration between marketing and product design teams, unifying everyone involved around shared objectives.

Once the various customer needs are identified, the product design process can address different jobs-to-be-done directly. This approach alleviates painful disconnects between departments, and positions an entire brand to better serve its customers.

How can your brand make similarly transformative changes, utilizing the jobs-to-be-done framework to understand and influence consumer behavior? Additionally, how can your business embrace its full jobs-as-progress potential, inviting all internal stakeholders to partake in the effort?

The answers to these questions will clearly differ significantly in different contexts. But no matter what your business does, here are some essential areas of inquiry your team can explore to assess your customers’ most fundamental needs.

The Situation

What is the environmental context in which consumers choose your product or service? In terms of location, timing and other situational factors, how do people encounter your brand in the course of their daily lives?

These background details may seem inessential, but they sometimes deliver powerful clarity about the nature of the job-to-be-done. Remember the moral of the milkshake story: The product’s appeal existed within a particular time and space, a context the chain had overlooked entirely.

To recognize the importance of situational factors to the role your brand should play, look no further than your interpersonal experiences. When you’re seated next to a stranger at a dinner party, the job-to-be-done might be to ask them polite questions about themselves. Do the same to a stranger in an elevator, and you’ll probably get some dirty looks.

Brands must exercise the same deference, respecting their customers’ reality. Context dictates the job-to-be-done.

The Struggle

Within the consumer context you’ve identified, which tensions or conflicts define the experience? Are certain priorities in contradiction? Is a tradeoff inevitable to some extent?

One recurring struggle customers encounter is the clash between convenience and intention. Our long term aspiration may be fitness, but our immediate desire points towards pizza. We want to save money, but a new pair of shoes sound pretty good. In cases such as these, the job-to-be-done will necessarily reflect the presence of conflict.

Can your brand help customers navigate these difficulties, ultimately empowering them towards decisions they’ll be proud of? If so, that’s your job to be done.

Current Solutions

Within your business category, what is already being offered to consumers to meet their various needs? More importantly, which products or services are being “hired” consistently?

The success of existing products can indicate a lot about the nature of the job-to-be-done. Likewise, failed attempts in the category can be quite instructive: Noticing what they lack may be necessary to avoid the same fate. In this way, you can begin to establish the “hiring criteria” consumers are using to make purchase decisions in your space.

Yet be careful not to rely too much on precedent, lest it obscure new possibilities. As you study previous efforts from competitors and your own brand, question assumptions about why they soared or sunk. You may discover interesting areas of uncertainty worth probing. Moreover, you may just find a different way to do the job entirely.

Discovering Jobs Your Brand Can Do

These areas of exploration can begin eye-opening discussions for any brand, illuminating potential for improvement and growth. Simply engaging the jobs-to-be-done framework for understanding customer decisions is a meaningful step in the right direction.

Still, this journey of inquiry can be both complex and confusing. Remember the murky topics this process can raise: Human needs and desires are hardly simple matters. Thankfully, you don’t need to investigate these questions alone.

With years of experience in the behavioral sciences, our team of researchers and subject experts can aid you in identifying the relevant jobs-to-be-done for your brand. Our services encompass a range of methodologies designed to produce implicit insights, the subtext below your company’s struggle and success.

As a result, we’ve helped a wide array of businesses and nonprofits connect with their customers on a trusting and sustainable basis. Many of the world’s most respected brands have benefitted from partnering with us in exploration.

Explore our services to see how we can help you discover the human truth of your customers. At Brandtrust, that’s our job-to-be-done.