One of the seminal psychological insights of the 21st century began with a jar of jam. Or rather 24 of them – a total that would soon prove problematic.

Psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper set up a display table in a gourmet grocery, featuring two dozen jam varieties. If shoppers sampled their wares, they received a coupon for the eventual purchase of the product. The next day, Iyengar and Lepper repeated this exercise but showcased just six types of jam instead. They sought to answer a simple question: Which strategy would produce more sales?

In fact, shoppers who saw just six jam flavors were roughly 6 times more likely to buy than those offered 24. Soon, the phenomenon of “choice paralysis” was enshrined in the doctrine of effective marketing: Offer consumers too many options and they’ll become overwhelmed, unmotivated to buy anything at all.

What if Iyengar and Lepper had asked shoppers how many options they’d prefer to see instead of conducting their experiment? If they had, the shoppers might have said, “I’d like to see 24. More choices can’t hurt, can they?”

Why Customers Can’t Tell You What Matters

The discipline of psychology revolves around a humbling admission: Without extensive experimentation and analysis, we lack a clear understanding of our own minds. In fact, no less than 95 percent of our thinking occurs at a subconscious level, driven by cognitive processes so subtle and swift we aren’t aware of them.

However, in marketing, this basic human truth is just beginning to dawn on the field’s leading minds. Many professionals continue to seek the keys to persuasion from a dubious source: the feedback of current or prospective customers about their own decisions.

Ample research suggests consumers’ explanations for their own thoughts and actions are incomplete at best and misleading at worst. In more traditional methods where direct questions are common, participants supply retroactive logic for impulsive choices. They give answers they sense are the right ones, responding to priming embedded in each question. They tell you they want to see all 24 flavors of jam, even though they don’t.

This powerful phenomenon doesn’t stem from dishonesty, but rather disconnection. Try as we might, we simply can’t perceive the processes that truly drive our choices. That’s why marketers must turn to consumer psychology for these insights instead. Only then can brands access, influence, and activate their customers’ real motives.

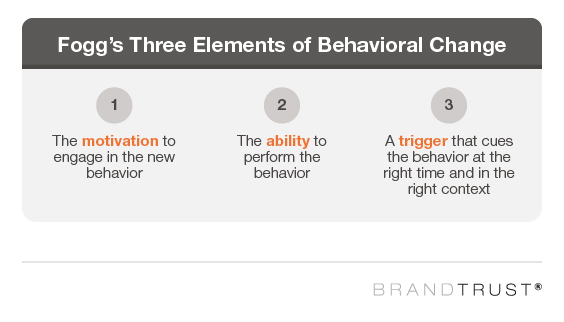

BJ Fogg, a visionary of behavioral design, describes three elements integral to a new choice or action – the result all marketers hope to achieve.

While each of these components is clearly essential, they can only be understood in light of the learnings of social science. Below, we’ll share five key insights from our study of consumer psychology to help you motivate, enable, and trigger customer engagement with your brand.

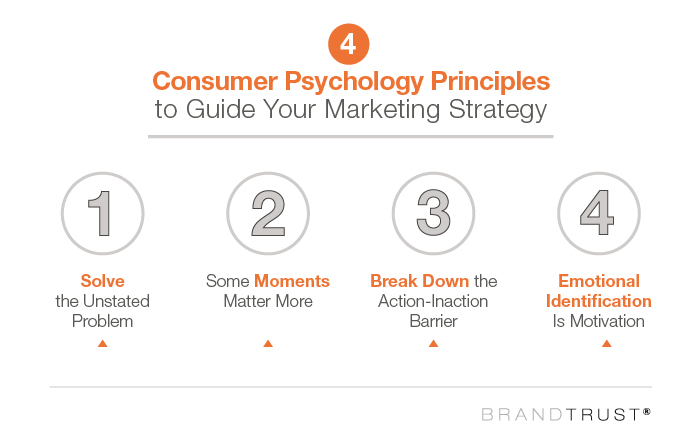

Solve the Unstated Problem

Most products and services promise some explicit function: Detergent rids clothing of its stains, plane tickets provide safe passage to your destination, and ground beef makes a good burger. But these literal requirements differ from the psychological needs brands can fulfill for their buyers if they’re observant enough to do so.

Consider one of the more emotionally involved spending choices a consumer can make: picking a getaway vacation. For a marketer in this space, the problems and solutions related to this purchase might seem obvious. Get the traveler to a destination they like for a price they can accept, and you’re all set, right?

But for the proprietors of The Body Holiday, a celebrated Caribbean resort, the consumer’s true quest is quite different. People seek getaway vacations as a respite from life’s most grating aspects, to restore their health and well-being. This psychological need can’t be meaningfully fulfilled in a few days, no matter how beautiful the beaches. So the resort focuses on imparting lasting tools of well-being to its guests, from dietary advice to meditation guidance.

This cure for what truly ails the traveler could never have been achieved by relying on the stated concerns of consumers alone. If they had, The BodyHoliday’s management might have fussed over a host of minor concerns – the details of drink packages or a discount for extended stays. But they would have missed their more fundamental service calling, rooted in their guests’ true psychological needs.

Example: In 1996, two separate companies launched in-home HIV test kits after investing heavily in their development. Both suffered anemic sales. In rushing their product to market, these companies had targeted a logistical problem: the inconvenience of going to a doctor to learn one’s status. But they ignored a deeper psychological need for comfort, support, and guidance in a potential moment of crisis, and failed accordingly.

Some Moments Matter More

Many brands adopt an unfocused approach to the experience of their customers. They aim to improve every single aspect of their business, often achieving only consistent mediocrity. Other companies are simply reactionary in their service acumen, scrambling to respond to all customer complaints without pausing to assess which are most meaningful.

Behavioral psychology suggests a more targeted approach to specific moments in their customers’ experiences would likely serve them better.

According to the work of Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, our minds retain only limited, representative snapshots of any experience. These snapshots coincide with an experience’s most emotionally intense and final moments, a phenomenon Kahneman terms the “Peak-End Rule.” Upon reflection, we virtually disregard all other pieces of a memory and form judgments using these peak-end instances alone.

For marketers and managers of customer experiences, this psychological insight demands a shift in emphasis. Don’t strive to make every piece of the brand experience good, but rather aim to make key junctures great.

Example: Administrators of the London Underground subway system identified a “peak” emotional experience among riders: the anxiety of waiting for one’s train. Standing on the platform, there was no way to know whether your train was 30 seconds or 30 minutes away, and thus whether you’d be late to your destination. This uncertainty was actually far more unpleasant than the waiting itself.

As a result, Underground officials installed digital displays in each station, announcing the time until the next train arrived. Customer experience scores soared in the following months.

Break Down the Action-Intention Barrier

Most of us can admit our actions and intentions often differ: We cheat on our new diet or don’t quite get around to certain chores around the house. But sometimes this disconnect occurs due to more mysterious aversions, many of which drive marketers crazy.

Why does an online shopper spend 30 minutes on your brand’s site, and then leave without buying the items added to his cart? Why do sales of a product stagnate when customer research revealed their reviews were glowing?

Once you’ve captured a customer’s interest, eliminating these barriers is a top priority, whatever they may be. But in many cases, brands underestimate the power of even small inconveniences to dampen purchase enthusiasm.

Behavioral economist Richard Thaler famously found requiring employees to select a 401(k) plan from several options was a major impediment to enrollment. In 2000, virtually no retirement plans featured automatic enrollment, which Thaler suggested would solve this problem. Today, nearly 60 percent of them do.

Is your brand hampered by some apparently minor obstacle to purchasing motivation? If so, it could be having an outsized impact on your engagement and sales.

Example: In 1999, Amazon patented “1-click” buying, which allowed customers to complete a purchase without re-entering their credit card details and address. By some estimates, relieving that small hassle increased sales by 5 percent – worth $2.4 billion annually.

Emotional Identification Is Motivation

Many brands advance value propositions founded on comparative benefits: We’re cheaper, faster, or better than our competitors. While these statements may be compelling in a limited sense, they’re also unlikely to be distinctive (every company toots its own horn). For many buyers, motivation will require an emotional recognition of shared personal values rather than calculated ones.

To accomplish this connection, marketers must understand the private and social aspirations of their audiences, and position their products accordingly. This process often involves delving into deeply embedded personal values. When customers consider your brand, does it confirm or contradict their vision of who they are? Perhaps more importantly, does it resonate with who they’d like to be?

Apple’s seminal “Get a Mac” campaign demonstrates the power of emotional identification explicitly. These ads were unabashed in the choice they posed: Would you rather be kind, calm, cool, and collected … or a flawed and fumbling fool? The campaign was so effective that Apple ran 66 iterations of the spot over more than three years.

Harnessing these motivating forces can seem intimidating, and many brands avoid them in favor of emphasizing narrower incentives, such as advantages in features or price. But this marginal appeal alone won’t often result in the most valuable outcome a brand can pursue: loyalty.

Example: In its classic “Choosy moms choose Jif” campaign, the peanut butter brand transformed a commodity into an identity. Suddenly, generic competitors looked like a compromise that discriminating mothers wouldn’t make. While we understand this tactic as problematic today, similar strategies can be applied to more positive (and politically correct) customer ideals in the present.

From Principles to Practice: Applying These Insights

While these concepts are crucial to effective branding and customer influence, the path from observation to action is often complicated. As marketers come to terms with the limits of traditional research methodologies, they’ll need to utilize alternatives rooted in social science to produce meaningful insights. Business challenges are invariably human challenges as well, and human truth requires expertise to access.

For nearly two decades, the Brandtrust team of social scientists and strategists has sought to provide the world’s leading brands with the conclusions they need to truly motivate their customers. We do so through an array of innovative methodologies, uncovering the drivers of consumers’ subconscious calculations.

From intimate interviewing processes to experiments conducted on a larger scale, our work is founded on the best practices of scientific inquiry. As a result, we furnish insights that are actionable rather than questionable, guiding our clients’ efforts toward human truth for their brands and their business.

To learn more about our research methods and strategic application to brands, explore our work with many of the world’s most respected brands.